|

|

|

The Physics of Jing

by John Chang

Martial arts bookshelves abound with books

and magazine articles about the ancient secrets of chi and

hidden mysteries of jing. For my part, I believe much of

this pseudo-mystical information can obscure the true nature

of important internal martial arts principles like chi and

jing. My personal hope is that the martial arts world will

increasingly understand internal martial arts principles

in more scientific terms. I believe that the truth can bring

just as great a sense of fascination and awe as mystical

legends.

Many legends tell the tale of the 90-year-old

master delivering a single punch that kills an accomplished

Kung Fu champion rippling with muscles in the prime of his

life. Legends often attribute the master’s seemingly

supernatural abilities to chi and jing as if the two are

interchangeable. Yet, the truth is at least as exciting

as legend.

The truth is that it really is possible for

the old master to deliver greater power in a single punch

than the muscle-bound opponent in his prime. Someone incapable

of lifting a 200-pound weight may deliver a punch with 200

pounds of pressure. It is possible for a female to exhibit

greater power than a male, and for a smaller person to wield

more powerful punches than a larger person. Better still,

the truth is that attaining fa jing (explosive power) does

not require spiritual oneness with the cosmos, but can be

readily explained by the laws of physics.

While chi stems entirely from the mind, jing

results when the mind precisely controls the body. Although

chi has often been equated with jing, the two are actually

quite different. Ultimately, after many years of practice,

the martial artist may combine the two together. I prefer

to begin my students with jing to prepare them for chi.

Later, I teach them to use chi to lead jing. Only much later

are chi and jing combined.

Jing is considered an “internal”

martial arts principle because it is mostly invisible. However,

this invisibility does not mean that jing is not the result

of the body’s physical movements. Jing is invisible

only because it is the product of very subtle alignments

in the body.

To understand the physics of jing, let’s

first look at the physics of an “external” punch.

External punches derive power from speed and body weight.

Since Sir Isaac Newton, we have known that inertia—in

this case, the transfer of power from fist to the opponent’s

body—is a function of mass and velocity. When the

fist carries a greater mass at a faster speed toward the

opponent’s body, the punch packs greater power. For

time immemorial, martial artists have maximized the power

of their punches by throwing their weight into their punches,

thus adding more mass to the punch, and by building their

muscular strength, thus developing the ability to hit the

opponent at greater velocity.

A punch that uses jing is quite different from

a punch that uses external power, but is still subject to

the same Newtonian laws of physics. Ideally, a punch with

jing uses the earth for leverage. A punch with jing uses

the mass of the earth as its base of power instead of the

mass of one’s upper body. Clearly, using the mass

of the earth for leverage can deliver far greater power

than will ever be generated by the weight of the upper body.

Unfortunately, there is also a hard truth behind

why the old masters of legends are always 90 years old.

Consistently producing jing is no trivial skill that can

be accomplished overnight, and often takes a lifetime of

learning and practice. To deliver a punch with jing, the

body must create a tight connection between the earth and

the opponent’s body. If this connection is broken

at any point in the body, the amount of power delivered

decreases dramatically. In effect, the martial artist must

turn his body into a continuous solid rod stretching from

the heal of the back foot to the first two knuckles of the

punching hand in the case of a straight punch. This is achieved

only by precisely aligning numerous bones, joints, and other

parts of the body. The connection between the earth and

the opponent is most often broken at the wrist, elbow, shoulder,

hip, knee, or ankle, but can also be broken at other points

along the continuum. The angles of the legs, body, and arms

can also greatly impact whether the power of the punch is

directed into the opponent.

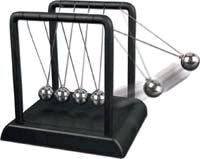

To illustrate the physics of jing, let’s

consider a popular experiment in physics known as Newton’s

Cradle. A series of metal balls are lined up, suspended

by strings. When the balls touch each other, creating a

solid connection from one end of the line to the other,

then dropping one of the end balls will cause the force

to be instantly transmitted to the opposite end ball while

losing very little power. Both end balls bounce back and

forth while the middle balls remain still. However, when

the middle balls are spaced apart even slightly, the connection

between end balls is broken and power is quickly lost when

traveling from one end ball to the other. Similarly, a martial

artist using jing uses his body to create an unbroken connection

of bones and joints between the ground and his fist. As

this connection expands with the punch, the mass of the

earth is used like a lever, directing the full power of

the punch into the opponent’s body.

Photo: Newton's cradle

While it is a pleasant thought that a smaller

person using jing can deliver a more powerful punch than

a much larger, more muscular person by using the mass of

the earth, it is a mistake to think that muscular power

plays no role in generating jing. Although muscular strength

is not as important for jing as it is for external punches,

muscles are still an important part of the physics of jing.

You’ll notice the careful use of the word, “leverage”

thus far. An external punch literally “throws”

body weight at an opponent, but jing does not throw the

earth at the opponent. Once a punch using jing has created

a solid connection between the earth and the fist, that

connection must quickly expand to deliver the fist to the

opponent’s body. While expanding, the connection must

never be broken. The faster the expansion, the more power

the punch will pack. Remember, power is always a function

of both mass and velocity, whether in an external punch

or in a punch using jing, and velocity is always a function

of muscular strength.

Muscular strength and whole-body coordination

are also important in creating what we refer to as zhen

jing in the 8 Step Praying Mantis community. Instead of

deriving power by using the earth for leverage, zhen jing

creates power from the sudden uncoiling of twisted joints.

Using zhen jing alone, one can generate great power while

sitting in a chair with no feet on the ground. As with using

the earth for leverage, zhen jing relies on muscular strength

to continue adding power to a strike as it is delivered.

Still, the 90-year-old martial artists among

us can take comfort in the fact that knowledge is generally

more important than muscle when using jing. There is an

old saying that, “external power is created by muscle,

but jing is created by bone.” Again it comes down

to simple physics. Even a slight break in the connection

between the earth and the opponent can significantly reduce

the power of a punch using jing. Similarly, power can be

greatly increased by improving how precisely the body’s

bones and joints are aligned, twisted, and uncoiled, and

by maintaining the correct alignment as the body uncoils

and expands to deliver the punch. Superior jing is created

only by a sharp mind with detailed knowledge and a lifetime

of practice.

|